Combatting Assessment Fatigue

No matter how dedicated or well trained, teachers cannot effect lasting, systemic change by themselves. Good teaching and good teachers need to be valued and supported by a rational system.

—Jacqueline Jones, Early Literacy Assessment Systems: Essential Elements

As an early childhood educator, you have undoubtedly noticed that this is not a particularly welcome time to talk about doing more assessment in the early child classroom. Teachers, parents, and students alike seem to feel that assessment has gotten in the way of teaching and learning. Assessment fatigue has set in among educators, who find themselves overwhelmed by the time and energy required to assess students’ learning and who experience a corresponding lack of time for instruction. This feeling of fatigue is driven primarily by a lack of alignment between curriculum and assessment and, additionally, by a misunderstanding of the uses of assessment. Assessment fatigue can be countered by having a conversation around the purposes and types of assessment and by creating a rational system that supports the alignment of curriculum and assessment.

Particularly in early childhood, assessment fatigue is heightened by current assessment approaches, which are characterized by over assessment in certain areas and underassessment in others. There is a tremendous amount of assessment in the areas of literacy and math, for example, but limited attention to monitoring students’ learning and growth in other areas such as social-emotional development, approaches to learning, and science. This imbalance hampers an educator’s ability to understand the full scope and developmental trajectories of children’s learning. Though many learning standards cover just two domains (i.e., literacy and math), other areas, such as those covered in Teaching Strategies’ comprehensive objectives for development and learning, have not lost relevance or importance for young children. Educators of young children ought to be given the time and resources to shape, monitor, and revise instruction across the full spectrum of development and to assess learning in all areas. The importance of educating the whole child has been recognized since long before I was a child, but creating a rational system that aligns and links curriculum and assessment to meet the needs of the whole child is long overdue.

So, who is responsible for creating such a rational system and what are the essential elements? For starters, a quick glance at the Professional Standards for Educational Leaders 2015 offers some insight. Standard 4 states, “Effective educational leaders develop and support intellectually rigorous and coherent systems of curriculum, instruction, and assessment to promote each student’s academic success and well-being.” In short, creating a coherent system that prioritizes curriculum and assessment is precisely the job of a school administrator—or any educational leader, for that matter.

Additionally, and perhaps even more important to consider than the instruction provided in the standard, it is well known that successful educational leaders create cultures that prioritize habits designed to support teachers who support children, as evidenced in this recent study of school principals.

How does an educational leader instill habits that support teachers to support children? First, a leader can ensure that best practices are well defined and commonly understood, which supports teachers and promotes alignment of quality curriculum and assessment. For instance, the initiative behind the development of First Through Third Grade Implementation Guidelines in New Jersey sought to define best practices in the primary years and assisted with the application of academically rigorous and developmentally appropriate curricular and assessment practices. Furthermore, the position statement Early Childhood Curriculum, Assessment, and Program Evaluation, jointly issued by the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) and the National Association of Early Childhood Specialists in State Departments of Education (NAECS-SDE), offers insight into the “why” of teaching and assessing young children and can be leveraged to create curricular and assessment coherence.

Simply put, the conversations about assessment and curriculum are inextricably linked. Offering teachers insight into the discussions occurring at a state and national level can support their knowledge of best practices and broadens their understanding that assessing in particular ways requires curricular approaches that accommodate embedded assessment.

While defining best practices is a significant first step in the alignment of quality curriculum and assessment, documents alone will not change practice or create rational systems. To inform and shape practice, targeted professional development is needed that incorporates three key elements that contribute to effective implementation of best practices and curricular and assessment cohesion. Professional development should do the following:

- Be ongoing and consistent throughout the year. Focus professional development offerings on teacher-led problems of practice that are relevant to teachers’ daily lives, such as room arrangement, scheduling, standards alignment, and monitoring growth over time.

- Involve both teachers and administrators. Focus on best practices and information tailored to teachers and administrators; the role of each will impact the other and affect implementation of best practices for both. For example, building schedules impact the implementation of classroom schedules.

- Employ a variety of methods. Include best practice videos, expert instructors, and Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) that are coordinated at the building and district levels to provide the relevant supports to implement newly learned practices.

Together, these elements of professional development help to create the opportunities and space needed to have conversations around the best ways to assess children’s learning.

As educators, we often speak of teaching children how to learn. When it comes to assessing their learning, we may need to do some more learning ourselves. Until our learning is linked to some changed behaviors that foster curricular and assessment coherence, the assessment landscape will not look rational to teachers and certainly not to children. Assessment fatigue is not preordained. It is time to turn that fatigue into an energy that moves each of us to be wide awake to the possibilities for and development of all children in our care.

Move beyond measurement

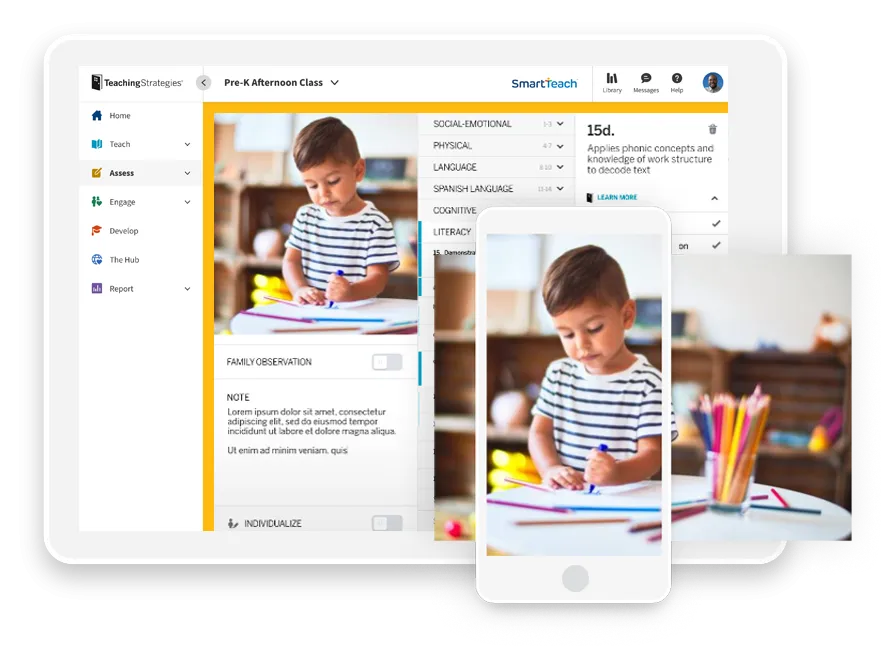

Inform instruction without disruption by embedding authentic, observation-based assessment into each part of the day with GOLD.