Studies vs. Themes: 5 Ways They Differ

Twentieth-century science fiction author Ray Bradbury is credited with saying, “Life is trying things to see if they work.” It’s a compelling insight into so many aspects of human existence, and it certainly relates to learning.

I came across Bradbury’s comment recently, written on the message board in front of a school near my home. My first thought was how inspiring it is to see this literal sign of schools embracing the idea of this being the business of schools—to function as a place where children are supported in exploring and investigating and trying things to see if they work.

My next thought was “Studies! This is what studies do!”

Studies are long-term, project-based investigations of materials that children find interesting and can explore firsthand in a variety of ways.

What Is the Difference Between a Study and a Theme?

Because studies are based on specific topics, they are sometimes confused with units or themes. However, this is both the beginning and the end of their similarities. In fact, one of the major differences between studies and themes is how and why particular topics are selected.

Topics for themes and units in early childhood education classrooms are often calendar-dependent, relying on seasons and holidays to determine what children will do and when. They are typically introduced year after year without regard for the unique nature of each year’s class members or their families, such as whether the children are interested in an annual unit on space exploration or dinosaurs. Some common themes are also incredibly difficult to facilitate with authentic materials that teachers can easily add to the classroom and children can readily explore: most teachers cannot bring animals from the zoo or the South Pole to school! They may also be abstract concepts—such as the five senses or rhyming—that are better explored throughout the year, regardless of the theme of the week or the unit.

Topics for themes and units in early childhood education classrooms are often calendar-dependent, relying on seasons and holidays to determine what children will do and when. They are typically introduced year after year without regard for the unique nature of each year’s class members or their families, such as whether the children are interested in an annual unit on space exploration or dinosaurs. Some common themes are also incredibly difficult to facilitate with authentic materials that teachers can easily add to the classroom and children can readily explore: most teachers cannot bring animals from the zoo or the South Pole to school! They may also be abstract concepts—such as the five senses or rhyming—that are better explored throughout the year, regardless of the theme of the week or the unit.

Study topics, by contrast, are intentionally chosen for their relevance to a class’s current interests and their potential for hands-on learning experiences in the classroom. Several criteria determine a good study topic, one that will encourage children to “try things to see if they work.”

- The first is that studies are long-term.

Studies typically last several weeks—often a month or more. However, study work never takes over that entire time. In fact, while there are special times each day during which we recommend that the teacher engage in discussions and experiences related to the study (such as the morning meeting), the study also leaves plenty of time to talk and learn about other knowledge, skills, and abilities unrelated to the study topic. - Studies are project-based.

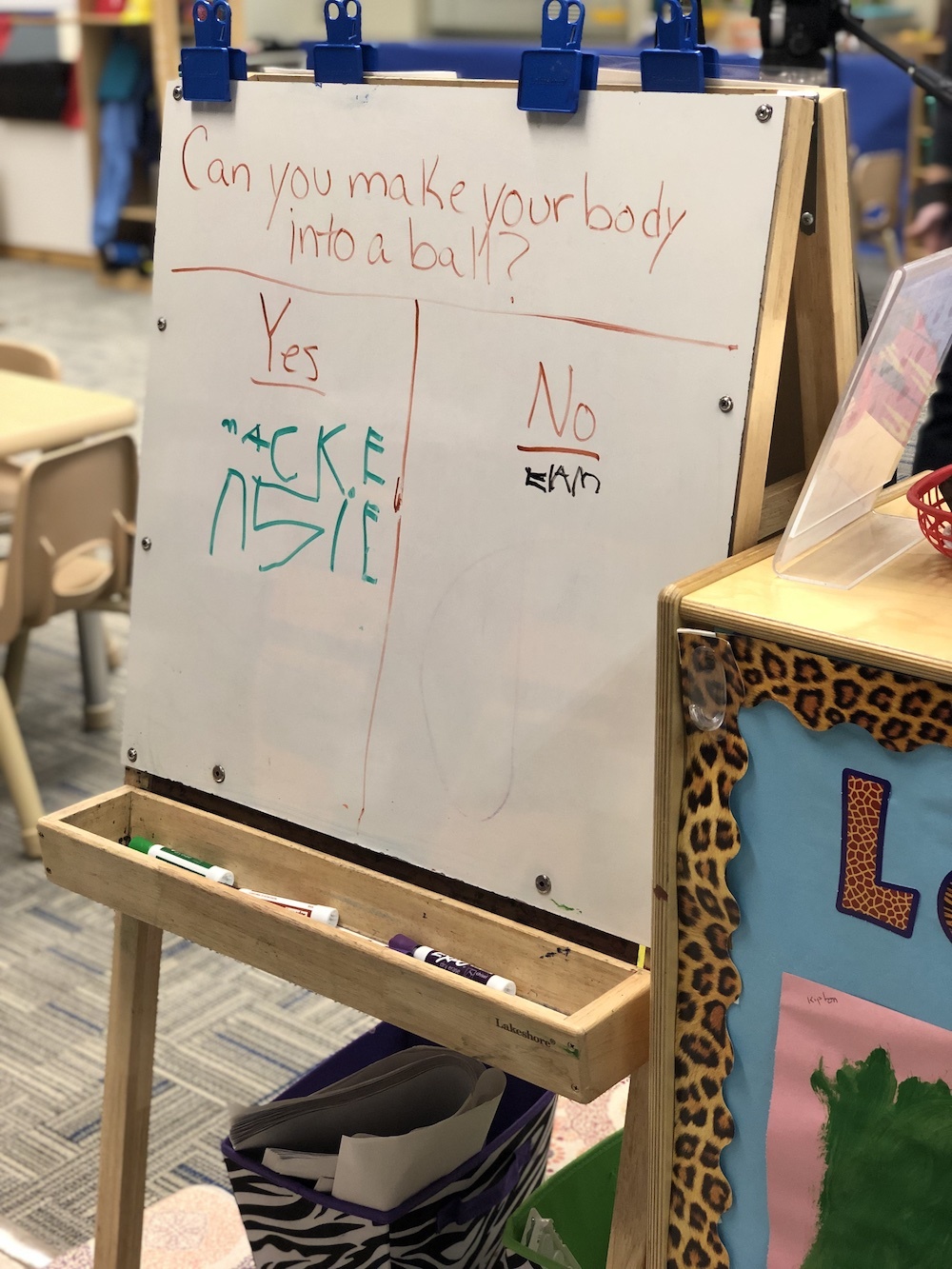

In project-based learning, children gain a deeper understanding of a real-world topic by actively exploring it. The knowledge learned and skills developed during project-based learning are almost always applicable to other topics and situations, not just those directly related to the current topic.  Studies include multiple investigations, during which children work to find answers to questions related to the study topic.

Studies include multiple investigations, during which children work to find answers to questions related to the study topic.

Teaching Guides for studies are built around helping children discover answers to relevant questions that we know they typically find interesting. You and the children in your class are always free to investigate questions other than the ones already described in the Teaching Guide; this responsive flexibility is another distinguishing characteristic of a study.- Studies relate to topics that children find interesting.

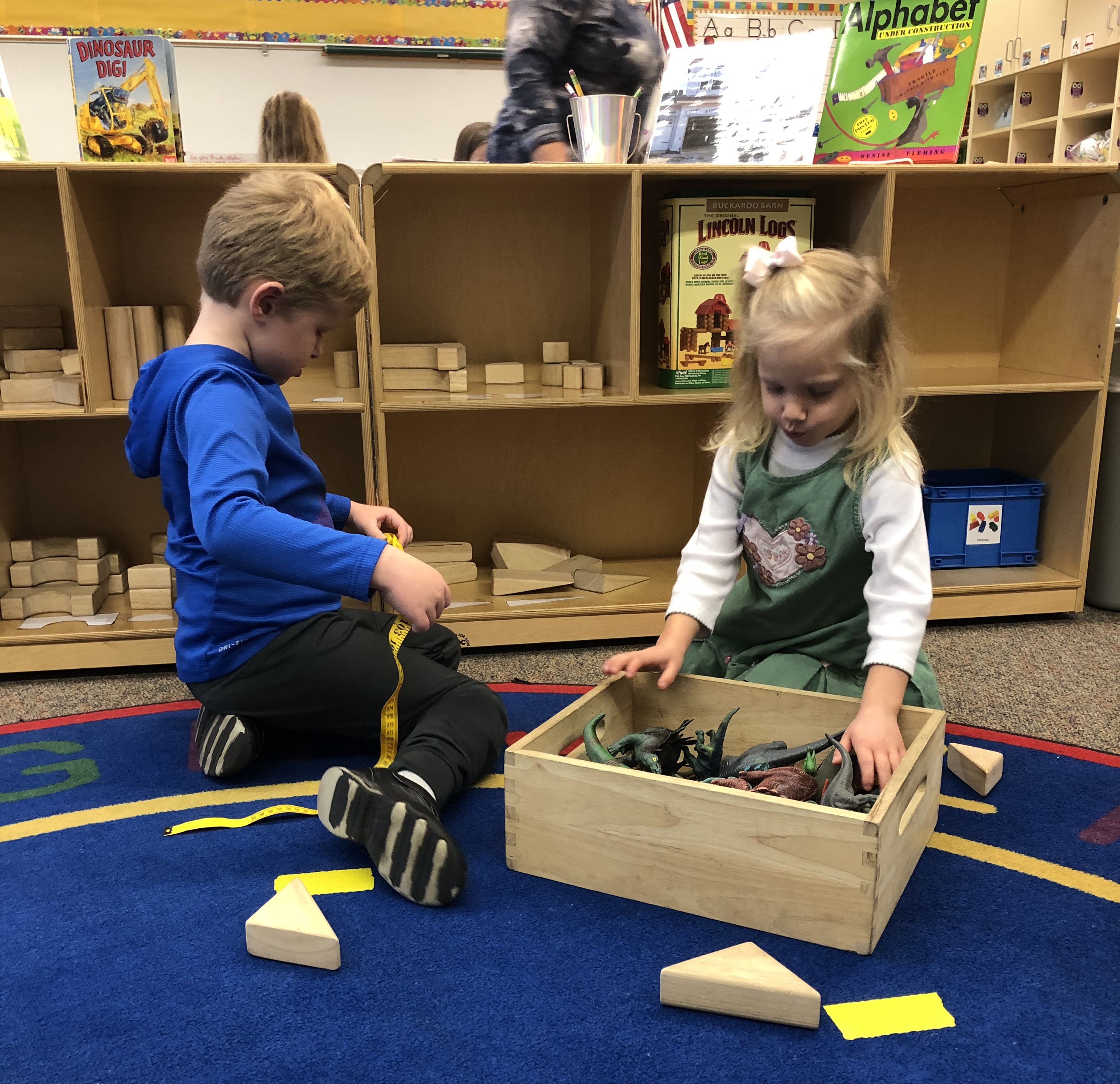

While children are often curious about a wide variety of events and materials, those that are suitable for studies are both rich and robust enough to hold children’s interest over an extended period of time and also age-appropriate and relevant to young children’s lives. - Studies include materials that children can explore firsthand in a variety of ways.

Children learn by doing. In fact, people of all ages learn by doing. And “doing” is the way to “figure things out.” Having multiple opportunities to explore multiple relevant materials for themselves means that children are free to leverage their natural curiosity and need for active engagement. They are also empowered to see themselves as capable learners who need not rely solely on adults to gain information. It’s also important to note that the study-based approach honors children’s need to both learn and to demonstrate their knowledge, skills, and abilities in a variety of ways.

Other important characteristics of a study topic are that they are respectful of cultural differences, offer opportunities for children to practice skills (literacy, mathematics, science and technology, social studies, and the arts) in meaningful contexts, and provide opportunities for families to become involved. When implemented with fidelity, the study approach will not only offer content learning but also empower children to think deeply, investigate rigorously, and question thoughtfully.

Ultimately, the test for what makes a good study topic is that it is worth learning about.

But What About the Dinosaurs?

I want to assure you that there is indeed a place to talk about, work with, and even decorate your classroom with “themes.” If children in your class love dinosaurs, trains, or princesses and unicorns, include some relevant books in your Library area and plastic toys in your Sand and Water area. Children often enjoy celebrations and holidays, so learn about the ones that are important to the children in your class and ask families for their ideas of ways to incorporate them into your classroom. Children are often fascinated by weather, the sun and moon and stars, and the changing seasons, so, again, make good use of the fact that studies don’t take over your whole school day and include opportunities for children to explore their other interests.

I want to assure you that there is indeed a place to talk about, work with, and even decorate your classroom with “themes.” If children in your class love dinosaurs, trains, or princesses and unicorns, include some relevant books in your Library area and plastic toys in your Sand and Water area. Children often enjoy celebrations and holidays, so learn about the ones that are important to the children in your class and ask families for their ideas of ways to incorporate them into your classroom. Children are often fascinated by weather, the sun and moon and stars, and the changing seasons, so, again, make good use of the fact that studies don’t take over your whole school day and include opportunities for children to explore their other interests.

But these themes (dinosaurs, trains, princesses, unicorns, weather, outer space, seasons) aren’t study topics because they don’t meet the very important criterion that distinguishes a good study topic: that children can explore them hands-on. While you may well want to lean into these interests from time to time, make sure that the topics chosen for studies lend themselves to experiences designed to drive deeper learning—or as Mr. Bradbury would say, to help children figure out what works.

A core element of The Creative Curriculumis its project-based studies where children actively investigate topics that are meaningful and relevant to their lives, so they investigate further. Because each topic is tangible, it drives deeper learning—all while the children are busy working and playing and finding out that they are confident, capable learners.

Inspire Children With Project-Based, Investigative Learning

Build children’s confidence, creativity, and critical thinking skills through hands-on, project-based investigations with The Creative Curriculum.

Learn more