The First Six Weeks of School: Knowing and Doing What’s Right

How are you helping children understand the concept of a “rule?”

In The Hub this week, we have been sharing ideas and strategies for supporting children’s understanding of classroom rules and why it is important for them to have a voice when it comes to making decisions that impact the classroom learning community. Today, we are highlighting some of our favorite ideas that our teacher colleagues shared this week.

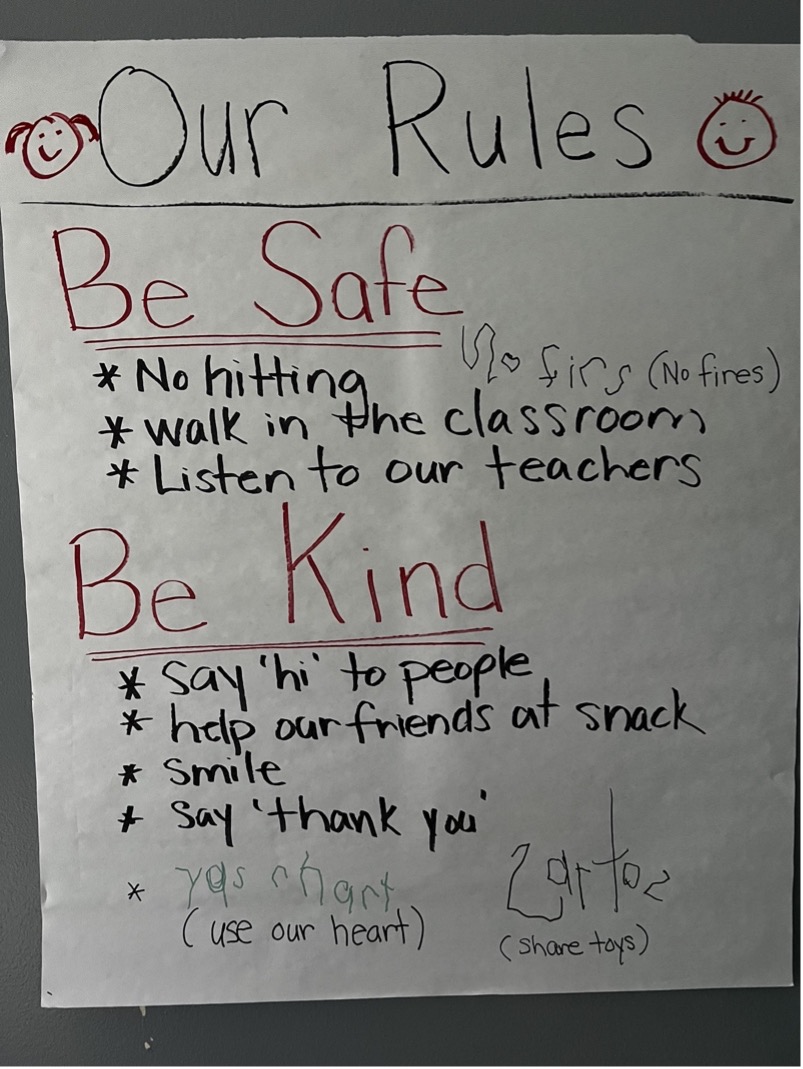

Like so many other teachers, we use time at the beginning of the year to develop our classroom rules together. Our program uses 3 universal Big rules and then each classroom makes their own little rules. Once we have come up with 3 little rules for each Big rule, I write them down. Then over the course of the next few weeks, I take pictures of the children modeling the expected behaviors. I create visual anchor charts from these pictures. Since the children have already been in school for a few weeks, we are able to talk about the different “rules” we have already been practicing – waiting our turns, sharing, walking inside, washing our hands, etc. We use real life examples to discuss how they felt when they were in the different situations. Providing the children with visual reminders of the expected behaviors means we can rely less on the verbal prompting to remind them and they can become more independent.

Cheryl W., Illinois

It is also vital that we, the adults, model the expectations of the classroom. I sometimes find myself “forgetting” one of our rules. When this occurs, I pose an open-ended question to encourage thinking about our class rules. In addition, we tell children what we want them to do (walking feet instead of running) and/or offer visual supports that use both text and images to show children what the expectations are. When a child needs support, we refer to the specific rule. If he/she is running, we point to the written rule and remind him/her that we use our walking feet. Once they have an understanding of why rules are needed and how the rules impacts them and our “classroom family”, they are more likely to follow them.

Colette V., New Jersey

Why is it important for children’s voices to lead classroom community discussions and decisions?

As I reflected on the conversations this week, my heart was brought back to four-year-old Ezra. Ezra would bounce into the classroom with confidence, had a robust personality, and was known for keeping the classroom “lively.” His first day of preschool proclamation was “I’m here, people, let’s get this party started!” However, by the end of the first week of school, I noticed a change in how the other children interacted with Ezra. Ezra didn’t keep his hands to himself or use his listening ears. This made the children anxious in their interactions with Ezra. Many 4-year-olds take comfort in knowing and adhering to rules, and, to his classmates, Ezra was already testing the system I had created.

After another week together, there was a shift in the classroom dynamics as the children began telling Ezra what to do and how to do it. The confident child was becoming sullen and silent. After a mighty meltdown of “I’m never coming back here again,” what Ezra revealed next broke my heart. He shared that his mama told him to be kind, listen to the teacher, and be helpful in school. But when he tried to help Mary by painting a cloud in the sky above the tree she had painted, she scolded him and told him he wasn’t respectful. When he added a block to Avery’s tower, the tower fell over, and Avery told him to keep his hands to himself.

In that moment, I realized that Ezra was doing exactly what his mother had asked of him and that the rules that I had fashioned for the classroom were being interpreted by the children without patience, understanding, or communication. “Why weren’t the children learning how to be respectful and responsible classroom citizens?” I had wondered. It turns out, I was expecting too much too soon from a class that I had not prepared to be a community.

I was making all the rules. I was instructing children on where to put their materials and how to play with them. Every time someone sneezed, I told them to go wash their hands. It was a light bulb moment for me that changed the classroom culture for all the years that followed.

I went back to The Creative Curriculum for Preschool, Volume 1: The Foundation, and I realized I hadn’t fostered a classroom culture that felt safe and predictable. The children didn’t understand the rules or how to talk to each other about them because I hadn’t offered them the opportunity to be part of conversations about expectations that made sense to them. We hadn’t taken time to develop trusting relationships before implementing rules.

Involving children in deciding the rules is a powerful way to encourage them to share responsibility for the classroom; however, when following the guidance recommended in The First Six Weeks, Building Your Classroom Community Teaching Guide, this doesn’t happen until day nine so that the children and the teacher have time to develop relationships first. When you are ready to have conversations about classroom expectations, you can implement a strategy called “big rule, little rule” to help guide a discussion with children that will produce classroom rules that everyone will agree with and still establish essential expectations regarding children’s safety, interactions, and care for the classroom environment.

First, keep three or four simple, positive “big rules” in mind during the conversation, such as “Be respectful” and “Be safe.” These are the non-negotiable rules you already need as the teacher to create a safe community. Then, as you ask the children what rules they think are important to have in the classroom, you can connect what they say back to the “big rules” and demonstrate how they provide positive instructions that will help children follow the “little rules” regarding specific behaviors. In my case, when I asked the children what rules they should have and Mary said, “No painting on my paper,” I was able to restate Mary’s idea in a way that focused on what the children could do rather than what they could not do: “It sounds like we want to be sure to respect others’ work. We do that by putting paint on our own paper. I will write ‘Be respectful’ as one of our big rules. How else can we be respectful in our classroom?”

First, keep three or four simple, positive “big rules” in mind during the conversation, such as “Be respectful” and “Be safe.” These are the non-negotiable rules you already need as the teacher to create a safe community. Then, as you ask the children what rules they think are important to have in the classroom, you can connect what they say back to the “big rules” and demonstrate how they provide positive instructions that will help children follow the “little rules” regarding specific behaviors. In my case, when I asked the children what rules they should have and Mary said, “No painting on my paper,” I was able to restate Mary’s idea in a way that focused on what the children could do rather than what they could not do: “It sounds like we want to be sure to respect others’ work. We do that by putting paint on our own paper. I will write ‘Be respectful’ as one of our big rules. How else can we be respectful in our classroom?”

Post the rules within the classroom and refer to them often by continuing to use the “big rule, little rule” strategy. When you need to encourage or correct a specific behavior, you can refer to a “big rule” the children agreed to as part of the classroom community to explain the “little rule” the child needs to follow in the moment. Consider, for example, “Be safe. Walk inside the building,” or “Be respectful to others. Keep your hands to yourself when you are feeling angry.” Adapt the rules when necessary. Children are more likely to take ownership of responsibilities when they have been part of the conversation.

Every child and every community are unique, and rules and their implementation will vary from class to class and community to community. The effort that you put into helping children create and understand these rules now will help build a wonderful community throughout the rest of the school year.

So, how are you helping children understand the concept of a rule?

Interested in joining the conversation?

Teachers with access to the Teaching Strategies platform can join conversations with other educators in The Hub’s First Six Weeks Forum.

About the Author: Laurie Kreg

About the Author: Laurie Kreg

Laurie has served as a program director and lead teacher for a high-quality private preschool while also supporting classroom teachers, program coaches, and administrators in creating a classroom community. She is currently a Subject Matter Expert with The Hub.

Laurie says that her favorite memories from the last four decades come while reflecting on her role as an active partner in play with children. Whether as teacher or coach, she still watches in amazement and with great joy the learning that takes place when children are gifted opportunities to become excited and curious architects of their world.

–

About the Author: Laurie Kreg

About the Author: Laurie Kreg