Why I Don’t Have a “Letter of the Week” Anymore

Letters and Words

I used to think I was an effective preschool teacher when every child in my class had earned 52 checkmarks for recognizing all 52 letters of the alphabet. (Yes, there are 52: 26 uppercase and 26 lowercase). Children would sit “crisscross applesauce” for more than 20 minutes at a time, reviewing and “learning” a letter each week.

I spent hours preparing worksheets, activities, and assessment checklists and gathering books focused on the letter P when the children’s names were Grayson, Timothy, Rashawn, Micah, Sofia, Marquese, Natalie, and Britany. The point is that no one in the class had a letter P in their name, so why devote a whole week to the letter P? Well, we just finished O, and in alphabetical order, it’s O, then P, and then Q. (I had to sing it to make sure. Did you?)

I thought alphabet knowledge (recognizing and naming each letter) was imperative to “preparing children for kindergarten” and teaching children how to read. So, I would sit with each child one-on-one to “assess” their knowledge of the alphabet by displaying letters out of their usual sequence and asking the child to identify each one. When a child could identify all 52, I pronounced him “ready.”

But what does this kind of “ready” have to do with reading? It turns out, not much.

I have since realized that learning to read requires the development of a richer set of skills than simply being able to name letters in activities that are devoid of any meaningful context. The time I spent creating and implementing these activities—not to mention the time the children spent engaged in them—could have been used far more wisely. Now I know that children need phonological awareness skills along with alphabet knowledge to be successful readers. I also know that these skills can be explored and developed through authentic, meaningful, play-based learning experiences.

So I don’t do “Letter of the Week” anymore.

I also no longer

- remove children from their learning in the name of one-on-one assessment,

- give letter worksheets that ask children to color in apples to learn about the letter A, or

- take time to cut out 20 large, A-shaped papers so that children can glue apple seeds to them.

The important part here is that not only did I have a gut feeling that these activities weren’t really teaching children to read, but that I came across compelling research that convinced me that nothing about Letter of the Week was providing intentional, authentic, hands-on literacy learning.

What Changed?

The children’s faces showed me their disdain for this ultimately meaningless work. Still, the realization that I was wasting learning time took me many years, many tears, and many trainings. Finally, a couple of things helped me see the light. One was the work of Lisa Murphy, lovingly referred to as “the Ooey-Gooey lady,” where she shared great research around playful learning. I also completed a book study with fellow colleagues where we examined alternatives to adapt our current thinking.

The other was taking the time to consult The Creative Curriculum for Preschool, Volume 1: The Foundation and Volume 3: Literacy. The information in these research-based volumes opened my eyes to the disservice I was doing to myself and to the children in my class. I was wasting time prepping worksheets and activities that were not authentic, play-based, hands-on learning experiences.

Children need many opportunities, all day and every day, to explore concepts related to the knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary to become competent, confident readers and writers. One of the components of reading instruction is letters and words, but it is just one. (The others include phonemic awareness, phonics, word recognition, and vocabulary.) Functional knowledge of letters and words also requires far more than being able to recite the ABC song.

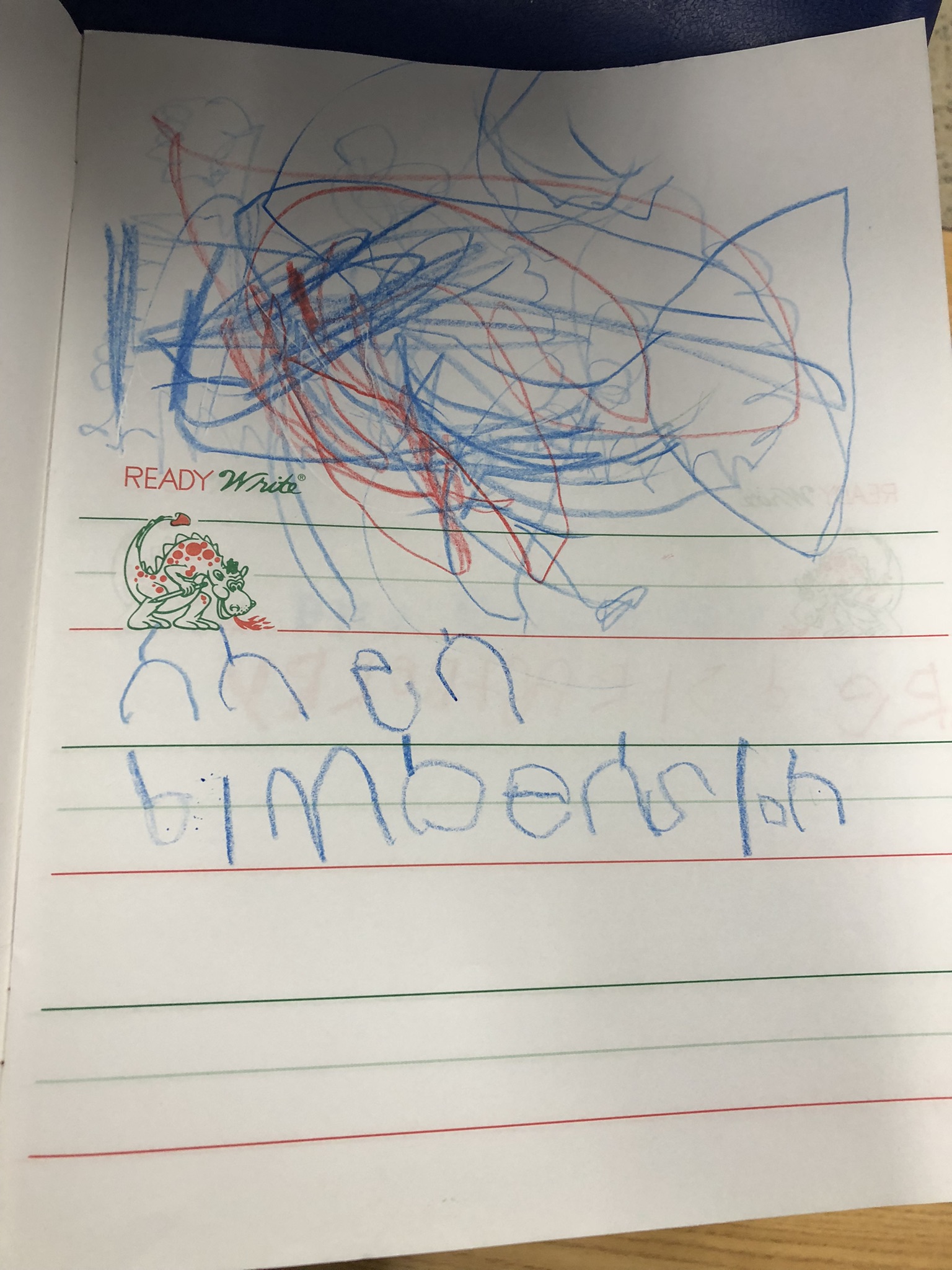

The most important letters to any child are those in their name. Once a child feels confident in writing and reading those letters, they take great pride in doing so repeatedly, thus providing an authentic reason to practice writing letters. The child also learns to attach sounds to those letters in a deeply meaningful way.

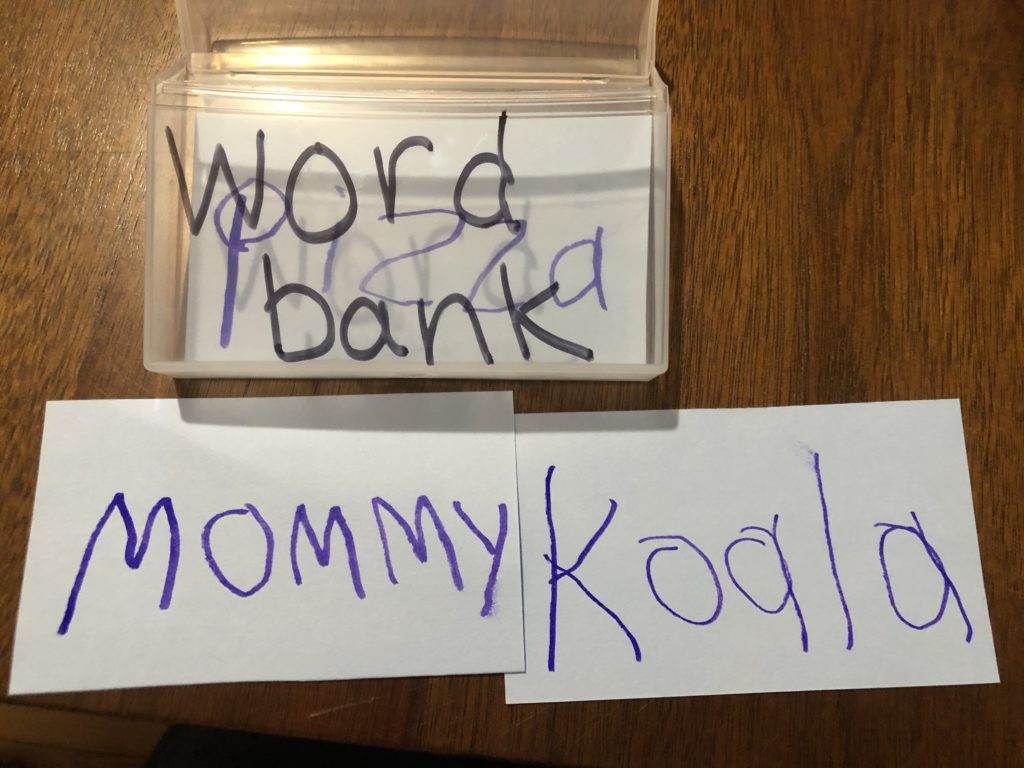

To determine if children are “ready to read,” offer to create a word bank for them and simply ask, “What words do you want to read?” The answer may be “Poop,” but who cares? They are reading! Furthermore, if children say something like this, they will finally have an authentic reason to learn about the letter P—what it looks like, what sound it makes, and how it can be useful to them, even if it’s not in any of their names.

To determine if children are “ready to read,” offer to create a word bank for them and simply ask, “What words do you want to read?” The answer may be “Poop,” but who cares? They are reading! Furthermore, if children say something like this, they will finally have an authentic reason to learn about the letter P—what it looks like, what sound it makes, and how it can be useful to them, even if it’s not in any of their names.

Listen for a child asking, “What does that say?” and “How do you spell…?” Those questions indicate that they realize that letters combine in specific ways to make words and that words carry meaning. You will also know that children are interested in learning to put letters together for themselves.

The Impact on My Practice and Classroom

Once I decided to cease the largely ineffective practices related to Letter of the Week, I replaced them with more intentional, play-based learning experiences that led to increased learning. I gained both instructional time and personal time (who doesn’t want more time?) when I stopped creating teacher-led activities that took me longer to prepare than it took the children to complete. I now have more time to play and laugh with children and build positive relationships with them, all while engaging in observation-based assessment.

Tips for Getting Started

If you, too, are ready to trade in Letter of the Week—or any other activities that neither build skills nor lead to a love of reading—for more meaningful experiences with words and letters, here are some quick tips for getting started.

- Remember that literacy is everywhere. Don’t confine it to your classroom’s Library area or one block of time in your daily schedule. Add signs to the Block area, menus to the Dramatic Play area, and books and writing tools and paper throughout the classroom.

- Children love writing with interesting-colored pens and markers, so provide writing utensils in many different colors, sizes, and even scents or shapes. Not only are they fun to use, but the smooth, fluid feeling of using pens and markers encourages writing.

- Provide a variety of writing surfaces, such as clipboards and personal dry-erase boards, that children can take anywhere, even outside. Model writing for authentic purposes every day.

- Help children create monthly class books about topics that interest them—from their families to their favorite foods, animals, or toys. They can also create books about letters, numbers, and their favorite words.

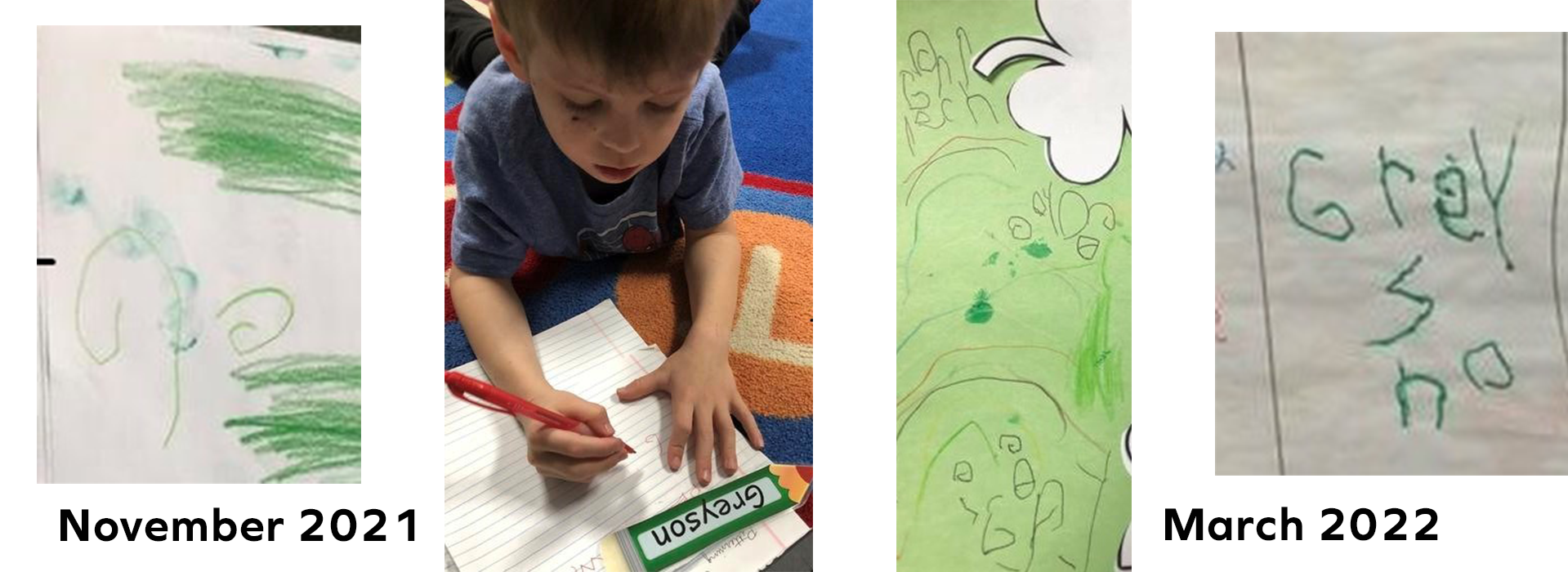

- The proof is in the documentation, and so is the assessment. Take a look at the changes in one child’s writing in just a few months, all because he was given many opportunities to practice in ways that he found meaningful.

Differentiate Learning for

Every Child

Individualize instruction and scaffold learning experiences to respond to each child’s strengths and needs with The Creative Curriculum.

About the Author: Crystal Kuharski

About the Author: Crystal Kuharski

Crystal Kuharski says her second grade career aptitude test said “you will be a teacher.” Since 2001, she has taught elementary and preschool-age children, directed preschool programs, and trained educators on best hands-on practices. After deciding she wanted to teach adult learners, she earned a Master’s degree in Early Literacy and Reading from Walden University and is currently a doctoral candidate with a dissertation on play in early childhood.